Entry cross-posted from Justia's Verdict.

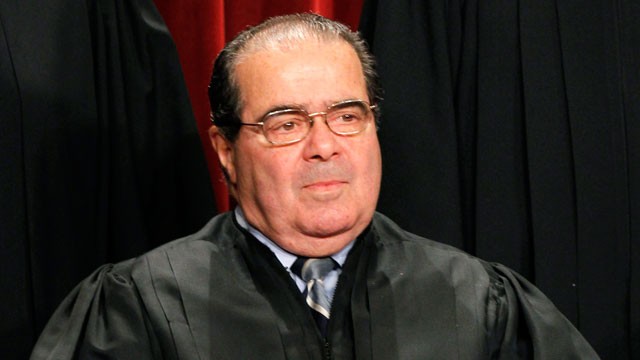

Justice Scalia made news last week for some remarks he offered concerning “easy” constitutional disputes. In particular, he suggested that challenges to the constitutionality of the death penalty, laws restricting abortions, and limits on the rights of gays and lesbians to engage in homosexual activity should be easy to reject because they fail the test of textualism/originalism, the mode of constitutional interpretation that he has said he prefers. In the space below, I analyze this mode, and discuss whether its use in the way Justice Scalia favors is, in reality, so easy.

The Essence of Originalism and Justice Scalia’s Application of It to Current Hot-Button Issues

Originalism is a term used, in modern times, to describe a particular approach to constitutional (and sometimes statutory) interpretation that seeks to understand and apply the text of the document as “intelligent and informed people of the time” of the document’s enactment would have. Justice Scalia has explained that originalism seeks to construe text “reasonably, to contain all that it fairly means.”

Under originalism, the meaning that counts is “the original meaning of the text” –”how the text of the Constitution was originally understood” by interpreters of the day. What the original draftsmen (that is, the people who actually wrote the words) subjectively intended might be evidence of what the words meant at the time, but any divergence between the drafters’ subjective intentions and the most likely understandings of those words at the time of enactment would be resolved in favor of the latter.

In any event, according to Justice Scalia, the “Great Divide with regard to constitutional interpretation [today] is not that between Framers’ intent and [original] objective meaning, but rather that between original meaning (whether derived from Framers’ intent or not) and current meaning.” Originalists reject the notion of “current meaning” and a “Living Constitution” primarily because, they argue, it vests too much discretion in modern judges and Justices to do whatever they please when they interpret the Constitution.

In a recent book event at the American Enterprise Institute, Justice Scalia reportedly said the following in applying his methodology to some legal disputes that have generated controversy and division on the Court over the past few decades:

The death penalty? Give me a break. It’s easy. Abortion? Absolutely easy. Nobody [at the time of the Fourteenth Amendment, whose due process clause has been used by the Court to recognize abortion rights] ever thought the Constitution prevented restrictions on abortion. Homosexual sodomy? Come on. For 200 years [including at the time of the Fourteenth Amendment], it was criminal in every state.

Are Things Really So Easy? Cases That Scalian Originalism Might Call in Question

Is Justice Scalia correct that his approach would make seemingly vexing constitutional disputes like these “easy”? For starters, I’m not completely sure that applying Scalia’s test to these realms would always provide clear answers over which historians would not argue; the task of discerning what words meant to intelligent and informed people of a bygone time is frequently far from simple. But even if Justice Scalia could convince me that his approach were easy in that it generates clear answers to the three particular disputes he mentioned, I don’t think, for reasons I explore below, that the application of his approach across the constitutional realm would make things easy in any larger relevant sense.

Before I discuss the complexities of applying originalism writ large and uber alles, let me make clear that that (as I have written before) I consider myself an originalist in that I think interpreting text without looking at the historical context that generated that text makes no sense. In other words, I think originalism, properly understood and consistently applied, is a very important component of legitimate constitutional interpretative methodology, notwithstanding my disagreement with the way Justice Scalia (and others on the Court) seem to have understood and implemented the idea of originalism in some settings.

But to say that originalism is important and helpful does not mean that it is easy. To see this, let us first look at what it would mean to say that all constitutional disputes should be analyzed and resolved by exclusive reference to originalism. It would mean, among other things, that the Supreme Court’s cases from the 1960s holding that states may not impose poll taxes or property qualifications on the franchise, because under the Equal Protection Clause and other parts of Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment there is an individual right to vote for legislative elections, are flawed. So too would be the cases holding, again under the Equal Protection Clause, that states cannot draw voter districts of significantly different sizes (thereby discriminating against urban voters); originalism would call into question the idea that the Equal Protection Clause guarantees “one person, one vote” in legislative elections.

These cases would be candidates for overturning because it seems pretty clear that no one at the time of the Fourteenth Amendment’s adoption in 1868 would have understood the words of Section One of that Amendment, including the Equal Protection Clause, to have anything to say about voting rights; the Amendment was written and explained to intelligent and informed interpreters of the day as being about “civil rights” (largely involving property rights), but not so-called “political rights,” such as voting and jury service.

Indeed, it’s hard to believe that informed and intelligent observers in 1868 would have understood the Amendment’s words requiring “equal protection of the laws” as forbidding racial segregation in schools or parks or water fountains. Nor would folks in 1868 have understood those words as invalidating limits on interracial marriage. Thus, cases like Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 (invalidating school segregation) and Loving v. Virginia in 1967 (invalidating bans on interracial marriage) might be vulnerable under Justice Scalia’s approach.

Even more vulnerable would be cases dating back to the 1970s holding that discrimination on the basis of gender is problematic under the Equal Protection Clause; the idea that people in 1868 would have understood the Clause to prohibit gender-based classifications is easily refuted by the historical record.

And, closer to the abortion setting that Justice Scalia mentioned in his recent remarks, it is hard, on originalist grounds, to explain Griswold v. Connecticut, the 1972 case invalidating Connecticut’s ban on contraception under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; it’s easy to say that people in 1868 would not have expected the Due Process Clause to have any application to bans on contraception that were then in existence, and that would persist, in most places, for decades.

Even the sexual sodomy setting that Justice Scalia adverts to is fraught with complexity. Justice Scalia says homosexual sodomy was made criminal for 200 years, so any claims of a constitutional right under the Fourteenth Amendment to engage in that activity are easily rejected. And homosexual sodomy was widely criminalized in 1868. But so was heterosexual sodomy! Does that mean that, under an originalist approach, a state could prohibit oral sex between a consenting man and woman in the context of a committed relationship today?

Some Non-Originalist Outcomes That Justice Scalia Has Embraced

Perhaps Justice Scalia could live with all the potentially disruptive results that I have described above, which might be dictated if we applied originalism to these realms. But originalism also calls into question some results that we know Justice Scalia has supported. For example, there is no strong originalist case against race-based affirmative action, and yet Justice Scalia has embraced the rights of non-minorities to challenge affirmative action under the vision of a colorblind Constitution. Justice Scalia has voted to aggressively protect commercial speech and the free speech rights of minors even though, at the time the First Amendment was adopted (and the time it was applied to the states through the Fourteenth), there is little to suggest that intelligent and informed folks of the day would have understood that these amendments would interfere with the myriad limits on commercial and children’s speech that were in effect at those times.

Or take the Eleventh Amendment, which the Court (with Justice Scalia’s support) has held protects States from being subject to liability for damages when state entities violate federal law, even though the text and history of the Eleventh Amendment refute, rather than support, any suggestion that intelligent folks of the day would have understood the Amendment to create such absolute immunity.

Counterarguments Make Things Harder, and Thus Further Undermine Scalia’s “Easy Cases” Claim

Some of the difficult questions I’ve raised above, about what a fully originalist legal world would look like, might be answered by creative rejoinders. For example, sometimes cases that are “wrongly reasoned” from an originalist perspective might nonetheless reach a result that is correct for other reasons. Here’s an illustration: Justice Scalia might say that the Eleventh Amendment immunity cases are correct not because they read the Eleventh Amendment properly, but because there is a general structural protection for states that emanates from the Constitution as a whole, putting aside the precise contours of the Eleventh Amendment.

But such a nuanced response takes us far beyond the realm of “easy.” And such a response might be available to support other, non-originalist, case holdings with which Justice Scalia may not agree. For example, some have argued that the “right to vote” and malapportionment cases may not jibe with original understandings of the Equal Protection Clause (on which they purport to be based), but are nonetheless defensible under, respectively, Section Two of the Fourteenth Amendment (a different part of that Amendment) and the Republican Guarantee Clause that is found in another part of the Constitution.

Another possible rejoinder, in some settings, is that States acting as outliers are vulnerable to constitutional challenge. Perhaps Justice Scalia would explain Griswold (and its protection of access to contraception) that way; in the Griswold case, Connecticut was virtually alone in that most other states had repealed or stopped enforcing their bans on contraception. But getting around originalism this way in Griswold creates complexities for cases involving homosexual sodomy, because very few states try to criminalize homosexual conduct in the way Texas did in Lawrence v. Texas (the 2005 case invalidating Texas’ law, over Justice Scalia’s animated dissent.) And certainly some states do look like outliers today with respect to various aspects of the death penalty, an area in which Justice Scalia finds it easy to reject claims.

Yet another rejoinder involves the level of generality at which one discerns the understandings of the intelligent people at the time of enactment. Take racial segregation. Folks who looked at the Equal Protection Clause in 1868 may have understood and expected that it would prohibit a system of state-imposed disrespect based on the race into which a person happened to be born, but they simply did not understand that segregation should be understood as visiting such disrespect. In instances like this, there may be clashes between the understandings of a constitutional provision’s larger aspirations and its narrower applications. Choosing to implement the former may not disrespect the values of originalism.

But once we start making moves like that, things get complicated. If the Equal Protection Clause is understood, in originalist terms, to be about an anti-caste principle, why cannot that principle be understood to extend to women, gays, and lesbians if they too are being disrespected simply because of the group into which they are born?

And past judicial precedent is an additional (though by no means the only other) complexity worth mentioning. Sometimes we might eschew originalism because there are already cases on the books that have decided the key questions. But, in this regard, it is interesting that Justice Scalia does not seem to feel bound by precedent in the three areas—abortion, same-sex conduct, and the death penalty—that he mentions.

My point here is not to disagree with any particular outcome that Justice Scalia supports in these or other areas—in fact, I sometimes agree with his constitutional bottom line, and at other times do not. But my goal here has simply been to suggest that all of this stuff is a long way from “easy.”