The BBC reports that the Internet has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Some, such as the Italian version of Wired magazine, have championed the Internet's nomination for helping advance "dialogue, debate and consensus."

It may seem laughable to give a Peace Prize to a communications medium, but there is reason to take the nomination seriously.

Alfred Nobel, in his will, announced that one prize should be awarded to "the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between the nations and the abolition or reduction of standing armies and the formation and spreading of peace congresses."

The Nobel Prize Committee has long awarded the Prize to associations, not just natural "persons"--including recently the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the International Atomic Energy Agency. Selecting the Internet would extend the prize further to an even more abstract entity, but it would still go to a human endeavor.

Has the Internet advanced the cause of peace? That still remains unclear, but there is reason to be hopeful. The Web makes possible an increasing sense of common membership in the world. The very nature of the "World Wide" Web, with its focus on interconnectedness and its disrespect for political borders or geographical distance, promotes this. The Internet, in this sense, promotes "fraternity between the nations."

The Internet also allows dissidents to escape local controls on speech. I explore this further in a forthcoming California Law Review article, Googling Freedom, which I will post soon. This may be the reason that Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi is cited as a supporter of the nomination of the Internet for the Peace Prize.

The Internet also allows dissidents to escape local controls on speech. I explore this further in a forthcoming California Law Review article, Googling Freedom, which I will post soon. This may be the reason that Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi is cited as a supporter of the nomination of the Internet for the Peace Prize.

There is of course the dark side of the Internet. Through this medium, terrorists have plotted their terror and arms merchants have found buyers. Nationalists have promoted jingoism.

Indeed, the Internet might permit individuals to limit themselves to a narrow informational universe, accessing only sites and information that confirm (and perhaps strengthen) our prior views. This is Cass Sunstein's argument, which I have critiqued in my paper, Whose Republic?, published in the University of Chicago Law Review. Where Sunstein worries about the "Daily Me" made possible by electronic intermediaries that deliver news tailored to a reader's tastes, I observe that, for minorities, the traditional media offer the "Daily Them" -- a vision of society focused on its dominant members.

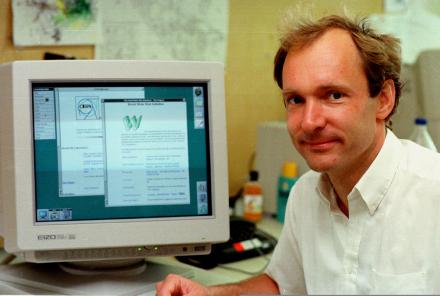

The BBC story notes that "[i]t is unclear who would accept the prize if the internet were to win." I would nominate Tim Berners-Lee, the man who gave the world the "World-Wide-Web," a visionary communications protocol that made the Internet popular beyond the relatively narrow confines of technologists.

The BBC story notes that "[i]t is unclear who would accept the prize if the internet were to win." I would nominate Tim Berners-Lee, the man who gave the world the "World-Wide-Web," a visionary communications protocol that made the Internet popular beyond the relatively narrow confines of technologists.

By raising the possibility of the Internet as a Nobel Laureate, I should not be misunderstood as endorsing such a choice. There are many worthy candidates, including Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, who languishes under arrest. Indeed, it is likely the case that these other candidates are more worthy of the prize--and that choosing them might have a greater likelihood of promoting the cause of peace.