[Cross-posted from California WaterBlog]

By Karrigan Bork

Co-authored with Peter Moyle, John Durand, Tien-Chieh Hung and Andrew Rypel

A recent biological opinion (BiOp) released by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) concluded that a proposed re-operation of California’s largest water projects will avoid driving the federally threatened Delta smelt to extinction. The plan proposes increasing water exports from the Central Valley Project and State Water Project, which will reduce water available for ecosystems and local uses. Both projects move water through pumps in the California Delta, a productive but sensitive ecosystem and home to the Delta smelt.

Under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), the FWS reviews federal agency actions to ensure that they will not drive listed species into extinction. In 2009, FWS reviewed the operation of the state and federal pumps that export water from the Delta and concluded in a BiOp that operation of the massive pumps jeopardizes the smelt’s continued existence. FWS required reduced pumping and other measures to protect the smelt, and those measure are currently in effect.

In 2019, the FWS again reviewed this new plan for the pump operations and concluded that many of the 2009 protections were actually not necessary and that the pumps could export significantly more water without jeopardizing the smelt. It draws this conclusion in two ways. First, the opinion notes that “recent abundance trends strongly suggest [the smelt] is in the midst of demographic collapse” and will likely go extinct without intervention. Based on this existing trajectory, the opinion concludes it won’t be the project’s fault when smelt disappear. Second, the opinion implies that, because agencies will spend $1.5 billion on habitat restoration, a production hatchery for smelt, and other measures, the net effect for the smelt will be positive. Based on these considerations, FWS concluded that the new operation plan would not drive the smelt to extinction, although it acknowledges extinction might happen anyway.

But the BiOp considers a very narrow question. The BiOp does not consider whether the plan is likely to improve the smelt’s status, and this BiOp in particular constrains its analysis so it does not meaningfully consider what is likely to happen to the Delta smelt under the new plans.

So, moving away from the narrow BiOp and considering the smelt in a broader context, what is going to happen to smelt in the wild? Is extinction likely? This essay explores some issues affecting Delta smelt and suggests possible futures. This blog is a short version of a longer white paper (with references) available at: https://watershed.ucdavis.edu/shed/lund/papers/FuturesForDeltaSmeltDecember2019.pdf.

The basic problem

The estuary where Delta smelt evolved no longer exists, and smelt are poorly adapted for the new conditions. Much of the water that once flowed through the estuary is stored or diverted upstream or exported by the south Delta pumps (Hobbs et al. 2017; Moyle et al. 2016, 2018). The smelt’s historical marsh habitats are now artificial channels and levees protecting agricultural islands. These hydrologic and physical changes make the Delta prone to invasion by non-native organisms, some of which disrupt food webs and confound restoration. Lower flows allow salts, toxic chemicals, and nutrients to accumulate. Harmful algae blooms occur regularly. As climate change further disrupts flows and increases temperatures, little historical habitat is left for sensitive species like smelt.

A tipping point

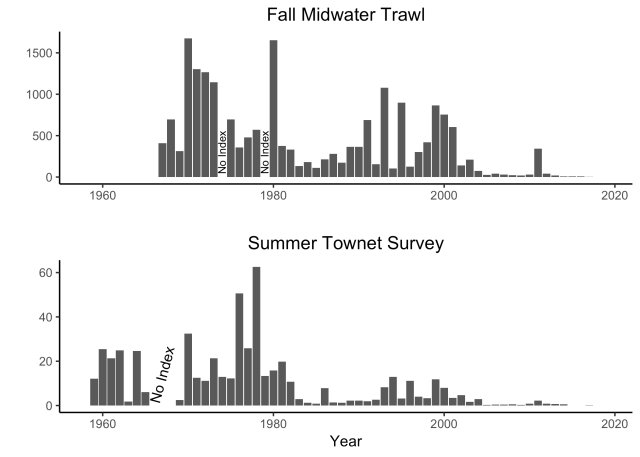

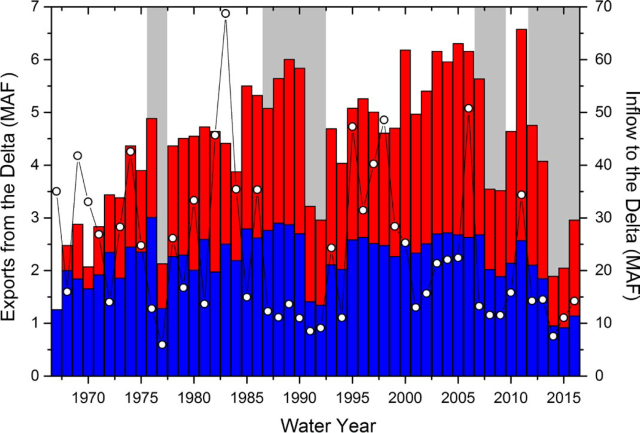

Smelt populations have probably been in gradual decline since at least the 1950s (Figure 1), but their population has collapsed since the 1980s, tracking the increase in water exports (Figure 2). This correlation is compelling, but other major system changes took place in the same period. In the late 1980s, an invasive clam spread through the Delta, removing much of the smelt’s planktonic food supply. Concurrently, invasive weeds spread across the Delta, transforming former Delta smelt habitats into clear, food limited, lake-like environments. From 1969-89, the Delta tipped away from good smelt habitat to a novel ecosystem unfavorable to smelt. This shift is practically irreversible, and the shift put the Delta smelt on a trajectory toward extinction as a wild fish. It is currently largely absent from surveys that once tracked its abundance.

Figure 1. Indices of Delta Smelt abundance in the Delta’s two longest-running fish sampling programs, the Summer Townet Survey (for juvenile smelt) and the Fall Midwater Trawl Survey (mostly pre-spawning subadults). Figure by Dylan Stompe.

Figure 2. Annual water export (left axis) from the south Delta by the State Water Project (red) and federal Central Valley Project (blue) in million acre-feet. Gray bars show droughts, when pumping was reduced primarily because of low inflows. Annual inflows of water to the Delta in million acre-feet (right axis) are open circles. Data: www.water.ca.gov/dayflow. Figure: Moyle et al. 2018 https://afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fsh.10014

Is habitat restoration the answer?

The BiOp relies in part on habitat restoration under California’s EcoRestore and other programs to support flagging smelt populations. There is little guarantee that this will make much difference to smelt, although many other native species will benefit.

First, the area under restoration is insufficient. Delta smelt originally inhabited an area about the size of Rhode Island, moving opportunistically to find appropriate conditions. Because Delta smelt are migratory and pelagic, smelt will overlap with restoration sites only occasionally. Successful habitat restoration would have to include multiple sites adjacent to water corridors, with abundant food and cool water, and in areas suitable for both spawning and rearing. Instead, the restoration approach has been more opportunistic than strategic, with restoration often focused on wetlands with willing sellers, regardless of suitability. We have little working knowledge whether we can build, connect, and manage these sites to benefit smelt.

Second, some projects rely on the idea that just creating tidal wetlands will be sufficient. It will not. Most Delta restoration sites are vulnerable to invasion by non-native species, which can subvert habitat solutions. Successful restoration sites require intensive, continuous management to meet even minimum expectations of restored habitat, and there is little incentive to actively manage “natural” restoration sites.

Third, current smelt populations are too small to be able to see an immediate (annual) response to habitat changes alone. Whatever steps are taken to protect smelt may be too little too late.

Finally, while water users hope that restoration provides an alternative to water use, this is not realistic. Successful restoration requires water flowing across the landscape. Moving water promotes the exchange of nutrients, controls introduced species, distributes food production, and creates habitat structure. Flows help restorations mimic natural environments and improves their effectiveness. Flows give managers better control of where Delta smelt end up during the spring, summer and fall. Habitat with minimal outflow is an empty promise.

If we are serious about providing the outflow required for habitat for smelt and other fishes, a substantial environmental water right is needed to provide reliable water to interact with physical habitat to produce food and shelter. Allocation of a sufficient water right is difficult to envision, given the current conflicts in the Delta, but California’s Bay Delta Plan, currently under development, generally proposes significant water for Delta fish, based on a percentage of the rivers’ natural flows. If this water were treated as a right under the control of an ecosystem manager, Delta smelt might have a chance of more than extinction avoidance—they might recover.

Hatchery Smelt

The BiOp also relies on hatchery supplementation of wild stocks to mitigate smelt impacts. The UC Davis Fish Conservation and Culture Laboratory (FCCL) has maintained a genetically managed Delta smelt population since 2008, but low wild smelt numbers complicate its operation. FWS allows FCCL to incorporate 100 wild Delta smelt into its population annually, to maintain genetic diversity, but recently the FCCL has been unable to capture 100 individuals. Without those fish, inbreeding might rapidly increase and add further uncertainty to the success of supplementation. Other hatchery supplementation programs, such as those for salmon, have had limited success in re-establishing self-sustaining wild populations. The smelt efforts will likely follow suit (Lessard et al. 2018).

Conclusions

Based on our experience and research in the Delta, any benefits from the habitat restoration and hatchery plans in the new opinion are too uncertain to reliably offset negative impacts of increased water exports. The Delta has changed so much that suitable habitat for Delta smelt is increasingly lacking. Large-scale restoration projects that provide habitat and food for smelt will at times need increased outflows. Desperate measures such as a production smelt hatchery and establishment of smelt in reservoirs may provide a veneer of ‘saving’ smelt for a while, but they seem unlikely to prevent extinction in the long run. In short, the smelt are likely to continue on their extinction trajectory. The following seem the most likely alternative futures for Delta smelt, in rough order of likelihood:

- Extinction of the wild population in 1-5 years, with a population of increasingly domesticated hatchery smelt kept for display and research purposes.

- Persistence of a small wild population in a few limited intensively managed habitats, until these habitats cease being livable from global warming and other changes.

- Global extinction after wild populations disappear and hatchery supplementation or replacement fails.

- Replacement of the wild population with one of hatchery origin, continuously supplemented.

- Persistence of wild populations as the result of supplementation and through establishment of reservoir populations.

The authors are at the University of California – Davis, Center for Watershed Sciences.

Further reading

Hobbs, J.A, P.B. Moyle, N. Fangue and R. E. Connon. 2017. Is extinction inevitable for Delta Smelt and Longfin Smelt? An opinion and recommendations for recovery. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 15 (2): San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 15(2). jmie_sfews_35759. Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/2k06n13x

Lessard J., B. Cavallo, P. Anders, T. Sommer, B. Schreier, D. Gille, A. Schreier, A. Finger, T.-C. Hung, J. Hobbs, B. May, A. Schultz, O. Burgess and R. Clarke (2018) Considerations for the use of captive-reared delta smelt for species recovery and research, San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 16(3), article 3.

Moyle, P. B., L. R. Brown, J.R. Durand, and J.A. Hobbs. 2016. Delta Smelt: life history and decline of a once-abundant species in the San Francisco Estuary. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science14(2) http://escholarship.org/uc/item/09k9f76s

Moyle, P.B., J. A. Hobbs, and J. R. Durand. 2018. Delta smelt and the politics of water in California. Fisheries 43:42-51.

Moyle, P.B., K. Bork, J. Durand, T-C Hung, and A. Rypel. 2019. “Futures for Delta Smelt”. Center for Watershed Sciences white paper, University of California – Davis, 15 December, https://watershed.ucdavis.edu/shed/lund/papers/FuturesForDeltaSmeltDecember2019.pdf